Home

The Mission

“ This writer wanted to compile a history of the area,

and present it in honor of the celebration of the bicentennial

of the founding of Mission San Miguel,

Arcangel in 1797.

This work is not an attempt to be an exhaustive

history; its purpose is to provide a fairly concise, one

volume history for the general reader. It is hoped that

this work would be useful to elementary and high

school students who are given exposure to local history. ”

Wallace V. Ohles

The Lands of Mission San Miguel

Chapture 1: Mission San Miguel Property and Padres.

by Wallace V. Ohles

Author and Historian

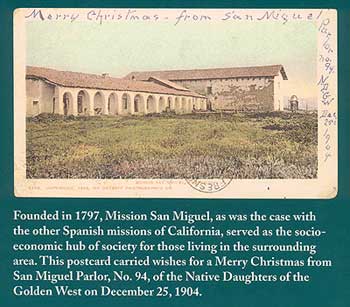

Mission San Miguel, Arcangel had been

founded on July 25,1797, by Father Fermin

Francisco de Lasuen, who was a successor of Father

Junipero Serra as Presidente of the missions.

Almost two years earlier, the site selection was being made

for the mission which was to be named for the "Most

Glorious Prince of the Celestial Militia, Archangel

Saint Michael."

Almost two years earlier, the site selection was being made

for the mission which was to be named for the "Most

Glorious Prince of the Celestial Militia, Archangel

Saint Michael."

Father Buenaventura Sitjar, of Mission San Antonio de Padua, along with Sgt. Macario Castro, Corporal Ygnacio Vallejo and a few soldiers surveyed the region, from the Rio Nacimiento to the Arroyo de Santa Ysabel, and for three leagues on either side. (A league was equal to 2.63 English miles.) They were looking for springs, good land and timber. The group which was surveying the region reported that water was available from Arroyo de Santa Ysabel, Arroyo de San Marcos, springs nearby and water pools among the willows along the Salinas River. Under the date of August 27, 1795, Father Buenaventura Sitjar reported the following to his superior.

“Stone for filling in the foundations of the

walls are sufficient in the hillsides of the mesa

itself and nearby; On the other side of the willow run,

in the hills about a quarter of a

league, are large rocks, some of which are

lime stone, but the Arroyo de San Marcos is

the place where are many lime stones like

those they burn at San Antonio.

There are so many of such large water

pools on the tracts of land they occupy that,

even if there were no spring whatever, with

only the water which enters them from the

Arroyo de Paso de Robles, and the water from

the rain, there would be water enough to supply

the Mission and its fields.”

Father Lasuen, Mission San Miguel's founder, had been born in Spain on June 7, 1736. He volunteered for the American missions at the age of 23. He landed at Vera Cruz, Mexico, and entered the San Fernando College in Mexico City; Under Junipero Serra as Presidente, Lasuen joined Father Francisco Palou on his trek as far as Mission San Gabriel, where Lasuen remained until 1775

After Serra's death, on August 28, 1784, Palou remained in California as interim president of the missions. Lasuen was appointed Presidente on February 6, 1785. He arrived in Monterey by January 12, 1786, and for the remainder of his life, Mission San Carlos Borromeo was his official headquarters.

During 1797, Father Lasuen founded four missions: San Jose de Guadalupe on June 11th; San Juan Bautista on June 24th; San Miguel, Arcangel on July 25th; and San Fernando Rey Espana on September 8th. Lasuen died at Mission San Carlos Borromeo at Carmel, on June 26, 1803.

San Miguel, Arcangel was the sixteenth of twenty-three missions established in Alta California, twenty-two of them by the Spanish government, and one under the leadership of Mexico.

William Zimmerman, in his 1890 work entitled A Short and Complete History of the San Miguel Mission, states that "Statistics of 1815 inform us that San Miguel, in subscribing for subsistence for troops in 1815, furnished wine and wool, and that home-grown cotton was woven in San Luis Obispo."

The subject of weaving brings up an interesting story which is related in Robert Archibald's book, The Economic Aspects of the California Missions. He states that Father Luis Martinez, of Mission San Luis Obispo, wrote to Governor Sola on March 22,1816, and requested the services of an Irish weaver named Henry who was being held in Monterey. In another letter, of March 31, 1816, Father Martinez wrote to the governor concerning his disappointment that the weaver had been sent to Mission San Miguel, instead of to Mission San Luis Obispo. How long this Irish weaver remained at San Miguel is not known at this time.

We have the names of some important people from 200 years ago - the first guards stationed at Mission San Miguel: Corporal Jose Antonio Rodriguez, Manuel Montero, Jose Maria Guadalupe and Juan Maria Pinto. These men made up the escolta, the escort, or mission guard.

The year 1806 saw the construction of 27 huts as living quarters for the Indians. A granary (65 feet long), a storage and carpenter room (42½ feet long) and a sacristy (23½ feet long) were constructed in 1808. In 1810, a house (61½ feet square) was constructed at Rancho La Playa at San Simeon.

During the year 1810, under the guidance of Padre Juan Cabot, thousands of adobe bricks were made and stored for use in the construction of the present day church structure at San Miguel. [When the mission was restored in the 1930s, some bricks were discovered containing the bodies of birds inside, instead of the usual straw. During what period of time these unusual adobe bricks were made is not known.]

Father Juan Cabot was generally known as "el marinero," the mariner, in contrast with his older, dignified brother, Father Pedro Cabot, of Mission San Antonio, who was called "el caballero," the gentleman. A house was constructed at Rancho Asuncion in 1812, and the next year a building (56½ feet long) was erected on Rancho El Paso de Robles, six miles south of the hot springs.

The year 1814 saw some building done at San Miguel. In 1816, the stone foundations of the present church building were laid at its site, which is three quarters of a mile west of the Salinas River.

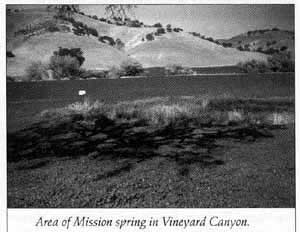

A house was constructed at Rancho del Aguage,

in 1815, near the Vineyard Spring; the rancho contained

an area of twenty-two acres. The vineyard, situated

at the distance of about three miles from the Mission,

was known as "La Mayor." The name Vineyard

Canyon comes from the location of this site. An adobe

house, with two rooms and a small parlor, was built

there in 1815 to house the vineyardist; his job was to

care for the Mission's vineyard, orchard and garden.

Built of adobe, and roofed with tiles, it was protected

from winter rain and summer sun by a tile-roofed corridor.

The floors were of earth. The location acquired

the name of Rancho del Aguage, or "Ranch of the

Wells."

A house was constructed at Rancho del Aguage,

in 1815, near the Vineyard Spring; the rancho contained

an area of twenty-two acres. The vineyard, situated

at the distance of about three miles from the Mission,

was known as "La Mayor." The name Vineyard

Canyon comes from the location of this site. An adobe

house, with two rooms and a small parlor, was built

there in 1815 to house the vineyardist; his job was to

care for the Mission's vineyard, orchard and garden.

Built of adobe, and roofed with tiles, it was protected

from winter rain and summer sun by a tile-roofed corridor.

The floors were of earth. The location acquired

the name of Rancho del Aguage, or "Ranch of the

Wells."

Slips of thorny brush, known as dahlia, were carried in from the Nacimiento area, and were planted in a circle below the spring. This planting formed a living corral for the sheep; it was too thick for the sheep to escape through, and no maintenance was required.

The mission's church building was completed about 1818. The corridor of the mission is said to have sixteen arches because this was the sixteenth mission to be established. In fact, there are only twelve actual arches; the four openings on the north end of the corridor are formed by square support pillars. Other construction which was accomplished resulted in homes for the neophytes, or Christianized Indians. Eventually the dwelling houses of the neophytes would cover an area of more than forty acres.

In 1825, weaving rooms were constructed at the Mission, and in 1830, the house (85 by 31 feet) was constructed at San Simeon. Hubert Howe Bancroft mentions that in 1829-1830, an Irish carpenter by the name of John Bones [or John Burns], was living at Mission San Miguel. This man had arrived in California in 1821, probably a deserter from one of the vessels which had sailed into Monterey; He was 23 years of age when he arrived in California. William Trevethan, who came to California in 1826, was a mayordomo at Mission San Miguel in 1829-1830. [The year 1840 found William Trevethan in Monterey; he petitioned for a lot on which to build a house. The lot was fifty varas by fifty varas, "situate in the rear of Sr Tomas 0. Larkin, and in a straight line with the Fort and Gualterio Duckworth's house." His petition was granted, "with the condition that he must run the line towards the pine woods (Pinal), leaving a street of 24 varas between the said lot and the house built by Sr Beltran." This is according to Book of Spanish Translations,Volume 2, page 339, in the County Recorder's office in Salinas.]

By 1832, construction, under the guidance of the Franciscan Fathers of Mission San Miguel, ended. The construction of the two-story building, 45½ by 30 feet, which has come to be known as the Rios-Caledonia adobe, was done under the auspices of the Mexican government, beginning about 1835. [Credit is given to Ella Adams for providing the dimensions of various mission buildings. The research had been done by Ed Wolf, a brother of Dorothy Kleck.]

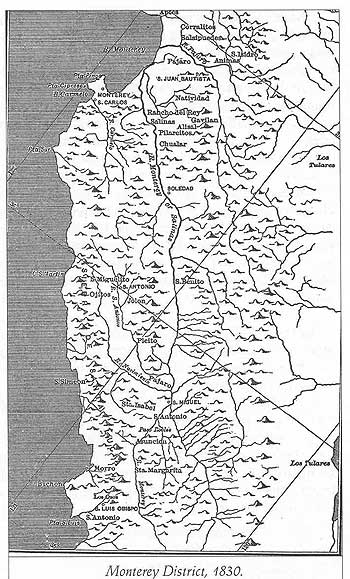

From Mission San Miguel's church building, the mission property extended 18 miles north as far as the southern portion of Mission San Antonio's land, and 18 miles south as far as the northern portion of Mission San Luis Obispo's land. The northernmost portion of San Miguel's property was Rancho San Bartolome, or Pleyto, a distance of seven leagues. The southernmost property of Mission San Miguel was Rancho La Asuncion, a distance of seven leagues. Mission San Miguel was said to be bounded on the east "by the Tulares" 66 miles distant, and on the west by the seashore 35 miles away

So, Mission San Miguel's lands extended 14 leagues, about 37 miles, from north to south; the lands extended 36 leagues, about 95 miles, from east to west.

We will take a look at the early missionaries who were responsible for the land and the Indians of Mission San Miguel.

Padre Marcelino Cipres (1769-1810) was first assigned to Mission San Antonio; in December of 1800, while on a visit to San Miguel, he suffered severe stomach pains, along with Fathers Juan Martin and Baltasar Carnicer. Everyone believed that the illness was the result of poisoning by the Indians.

Three Indians were accused by Father Cipres. A small military force from Monterey; under the charge of Gabriel Morego, was sent to investigate. The accused Indians were arrested. At Soledad, the Indians were able to escape, due to a sentinel being drunk on duty; The Indians were re-arrested; in 1802, the priest in charge asked that the Indians be released, after being flogged in the presence of their families. The priest believed that the Indians should be punished for "their boast of having poisoned the padres."

Father Cipres died at Mission San Miguel on January 31, 1810 and was buried in the sanctuary of the Church. Those who assisted at the time of his death were Fathers Juan Cabot, Pedro Cabot and Juan Martin.

On April 14, 1797, Padre Francisco Pujol (1762- 1801) had arrived in San Francisco. He served at Mission San Carlos from 1797 until 1800; from December 27,1800 until January 17,1801, he assisted at Mission San Antonio. On January 17,1801, he arrived at Mission San Miguel, and found that several missionaries there, as well as at San Antonio, had fallen ill. Padre Pujol also became ill and was taken back to San Antonio on February 27th. His companion, Padre Pedro Martinez, also fell sick but recovered. Padre Pujol died on March 15, 1801, and was buried in the church with full military honors. On June 14, 1813, Pujol's body was transferred, with that of Padre Sitjar, to a grave in the new church at Mission San Antonio.

The Concepcion had brought Padre Baltasar Carnicer (1770-?) to San Francisco, along with Padre Pujol. Padre Carnicer served at Mission San Miguel from July 9, 1797 until August 26, 1798. After serving for a time at Mission San Carlos, he was re-appointed to San Miguel. While there, in December of 1800, he, along with Padre Juan Martin, and the visiting friar, Marcelino Cipres, was attacked by the violent stomach pains. The three recovered; Carnicer became fearful of remaining at San Miguel, and was re-assigned to Mission San Carlos, where he arrived on March 29, 1801.

Padre Juan Martin (1770-1824) was first assigned to Mission San Gabriel, where he served from March 1794 until August 7, 1796. His next assignment was to Mission La Purisima between September of 1796 and August 6, 1797.

He had a long term of service at Mission San Miguel from December 3, 1797 until August 17, 1824. Padre Martin was responsible for building most of Mission San Miguel, including the church, which was begun in 1816. He was unsuccessful in convincing Governor Jose Joaquin Arrillaga of the need to found a mission in the San Joaquin Valley; Padre Martin died on August 29, 1824; on August 30th, Padre Luis Antonio Martinez gave ecclesiastical burial to the body of Padre Juan Francisco Martin.

The truth of the poisonings came to light with the publication, in 1965, of Father Fermin Lasuen's collected writings. According to Lasuen, the poisoning was caused from drinking mescal (a Mexican liquor) which had been stored in a copper container lined with tin, and not by any misdeeds of the Indians. This information is contained in a letter written to Padre Jose Gasol by Padre Fermin Lasuen, dated November 25, 1801.

[On November 13, 1912, two large marble slabs were placed over the graves of Fathers Martin and Cipres, within the sanctuary of the church. The mission bells tolled 41 strokes, in memory of the years of service of Father Cipres, missionary of San Luis Obispo who died at San Miguel, and 54 strokes in memory of San Miguel's great builder, Father Juan Martin.]

The poisonings were not the first major problems suffered by the Padres at Mission San Miguel. Padre Antonio de la Concepcion Horra (1767-?) became a problem almost from the very beginning. President of the missions, Padre Fermin Francisco de Lasuen, assigned Padre Horra to work with the experienced missionary; Padre Buenaventura Sitjar, for the founding of Mission San Miguel. Less than a month after the July 25, 1797 founding, Padre Horra began showing signs of insanity; The soldiers of the guard, and the Indians, were horrified and frightened, because the padre shouted and acted like a madman. The padre had fancied himself a great ruler; he compelled the Indians to discharge their arrows, and the soldiers to fire rounds of cartridges. It is said that Padre Horra wanted to kill ants which bothered him.

Father Sitjar conferred with Father Lasuen, and the President sent Jose de Miguel to the mission; he was to attempt, by gentle means, to persuade Padre Horra to accompany him to Monterey; 'Two surgeons at Monterey examined Horra and declared him insane; the governor made it official, and Horra was returned to Mexico. From there, Padre Horra was returned to Spain on July 8, 1804.

Padre Juan Vicente Cabot (1781-1856) arrived at Monterey on August 31, 1805. La Purisima mission was his first assignment. He ministered at San Miguel from October 1, 1807 until March 12, 1819; after serving at San Francisco and Soledad, he returned to San Miguel and served from November 7,1824 until November 25, 1834. During his first term at San Miguel, he was assistant to Padre Juan Martin; during his second term, he was in charge of the mission.

He sent a military expedition from San Miguel into the San Joaquin Valley on October 2,1814. The expedition went as far as present-day Visalia; on the way; several Indians were baptized. From November 4 through 15, in 1815, Father Cabot accompanied a second expedition, this one led by Juan de Ortega. A third exploration of the Tulare country was made in 1818. Although no mission was ever formed in the San Joaquin Valley; a significant number of Tularenos were baptized at Mission San Miguel.

In his report to Governor Jose M. Echeandia, in November of 1827, Father Juan Cabot informed him that "Between the east & north, this Mission owns a small spring of warm water & a vineyard distant two leagues." Other locations listed in this 1827 report were those situated to the south of the Mission. They included Rancho de Santa Ysabel (Saint Elizabeth), where there was a small vineyard, and Rancho San Antonio (Saint Anthony), where barley was planted.

The other listing included Rancho de la Asuncion (The Assumption), which had a spring with sufficient water for a garden, and Rancho del Paso de Robles (The Pass of the Oaks), where wheat was sown. At the last two named locations, there were adobe buildings, roofed with tile, for keeping seed grain.

It is this writer's belief that it is possible that two portions of Mission San Miguel's land acquired the popular name of Santa Ysabel; at the moment, this is simply speculation. The Santa Ysabel most familiar to us is the 17, 775-acre grant known as Rancho Santa Ysabel, located on the east side of the Salinas River, and south of the present-day City of Paso Robles. A possible location for another Santa Ysabel would be on the west side of the Salinas River at the location of some springs. Could either Mustard Springs or Mustang Springs, in the vicinity of the area northwest of Paso Robles be the location? What about the Indian Springs region, which extends to the Oak Flat area northwest of Paso Robles?

Eight miles of canals were said to have been built to carry water to Mission San Miguel. The springs at Santa Ysabel did produce an immense volume of water; however, Rancho Santa Ysabel was located 3 leagues from the mission, or about 7¾ miles. This is a subject of fascination that deserves much further research. This topic will be addressed further in the chapter on Rancho Santa Ysabel.

As we consider mission lands and what became of them, we need to consider an important distinction in our vocabulary; When we hear the word "rancho," what usually comes to mind is a land grant from the Mexican era of California history; The word "rancho" makes us think of a ranch, which would necessarily involve cattle or sheep; a rancho, however, could simply be a plot of farm land. It should be noted that not all ranchos became land grants. Some local examples are Rancho San Marcos (Saint Mark) and Rancho San Antonio (Saint Anthony).

Rancho San Marcos extended throughout the area known today as Adelaida. Rancho San Antonio comprised the flat farmland which is on the east side of the Salinas River, and extends from the Estrella River south to the gulch at today's Wellsona Road. Local residents refer to the gulch as "Shirt-tail Creek."

In the year 1818, the Tulare Indians seem to have taken the offensive against the missions in the Salinas Valley- - -San Miguel and Soledad- - -and also Mission San Antonio. In May of that year, an expedition under Sergeant Ygnacio Vallejo was sent against the Tularenos. According to Zimmerman, in his work A Short & Complete History of the San Miguel Mission, "There were two hard fights, one at Pleito on the Nacimiento river, the other to raise the siege of San Miguel in both of which the Indians were terribly punished and driven back to their territory;"

Communication between Mission San Miguel and its property on the coast was made by way of a cart trail. This cart trail had its beginnings with the aboriginal Indians at the coast creating regular trails over the Santa Lucia Mountains. These trails were used for centuries as trade routes of the Indians of the Salinas River valley and even further east.

Fraser MacGillivray; in his book about Adelaida,

states that "The survey maps of that time do show a

'trail from the coast to San Miguel' which crosses the

Peachy Canyon area and for several miles follows the

approximate alignment of Adelaida Road along the

east boundary of the present Chimney Rock Ranch in

a northerly direction, then easterly past the Santa

Helena Ranch, and northerly again to San Miguel.

This could have been a segment of the trail to Rancho

Santa Rosa which, for a time, was also operated by

Mission San Miguel."

Fraser MacGillivray; in his book about Adelaida,

states that "The survey maps of that time do show a

'trail from the coast to San Miguel' which crosses the

Peachy Canyon area and for several miles follows the

approximate alignment of Adelaida Road along the

east boundary of the present Chimney Rock Ranch in

a northerly direction, then easterly past the Santa

Helena Ranch, and northerly again to San Miguel.

This could have been a segment of the trail to Rancho

Santa Rosa which, for a time, was also operated by

Mission San Miguel."

MacGillivray goes on to state that "A consensus among the old timers seems to indicate that the mission trail to the coast entered the Santa Lucias in the vicinity of Lime Mountain and followed the general course of San Simeon Creek to the ocean."

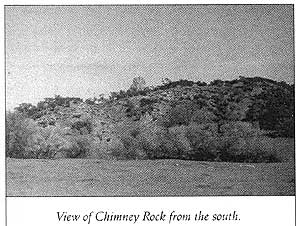

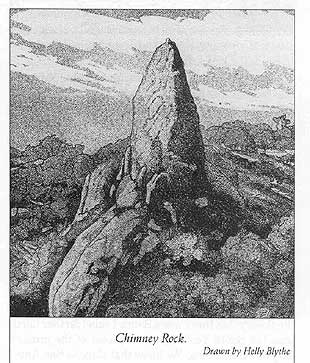

Chimney Rock is the most prominent rock outcrop

along the Mission Cart Road connecting San Miguel

to the coast.

Chimney Rock is the most prominent rock outcrop

along the Mission Cart Road connecting San Miguel

to the coast.

The Indians from Mission San Miguel were used to clear and construct the cart trail which would be adequate to haul logs from the headwaters of Santa Rosa Creek. This crude cart trail was extended to the ocean and to the Bay of San Simeon, most likely making use of the trade routes previously established by the Indians.

The sandy beaches near San Simeon were perfect for landing and embarking cargo. The bay had been used as early as 1800 for the purpose of dealing with unauthorized trading vessels. Ships were required, by the Mexican government, to pay duties at Monterey; this payment authorized a ship to trade anywhere in California until it had fIlled its hold with hides and tallow: If a ship's captain had not paid the duties, he was considered to be a smuggler.

Coves along the coast near Rancho Santa Rosa

were used as "drops" for hides to be picked up by

schooners taking part in the illegal trade along that

part of the coast. The seamen used the term "drop"

because hides were hauled to the edge of the cliff above

the landing cove, and were dropped to the sandy beach

below: On Rancho Santa Rosa, the drop amounted to

between 75 and 100 feet.

Coves along the coast near Rancho Santa Rosa

were used as "drops" for hides to be picked up by

schooners taking part in the illegal trade along that

part of the coast. The seamen used the term "drop"

because hides were hauled to the edge of the cliff above

the landing cove, and were dropped to the sandy beach

below: On Rancho Santa Rosa, the drop amounted to

between 75 and 100 feet.

In 1851, William Casey Jones' report to the Secretary of the Interior in Washington, D. C., said that Mission San Miguel's land extended to the seacoast, across the Santa Lucia Range to Rancho del Playa, a distance of between 12 and 14 leagues. This rancho was located at present-day San Simeon. This was the site of the first outbuildings which were constructed by workers from Mission San Miguel; the project began in 1810. An adobe house of two rooms was constructed there in 1814. In 1830, an adobe, measuring 85 feet by 31 feet, was built.

Jones' report states that to the south of Mission San Miguel was Rancho Santa Ysabel, three leagues off with a vineyard; San Antonio, where barley was raised, was at three leagues distance. Paso de Robles, at 5½ leagues, was where wheat was raised, and Asuncion was 6 leagues distant. The Spanish league was equal to 2.6 English miles.

The wording of the Jones report makes it sound like San Antonio and Santa Ysabel were both three leagues distant, or about half the distance to El Paso de Robles, which was about 8¾ miles from the mission. A map found in one of Bancroft's volumes shows a Santa Ysabel on the west side of the Salinas River. (It is worth noting that in this instance, Rancho Santa Ysabel and Rancho San Antonio were the same distance from Mission San Miguel; this could reinforce the theory that there was a Santa Ysabel farther north than the Santa Ysabel area southeast of the present City of Paso Robles. We know that Rancho San Antonio was not as far south as the Santa Ysabel that we associate with the area southeast of present-day Paso Robles.)

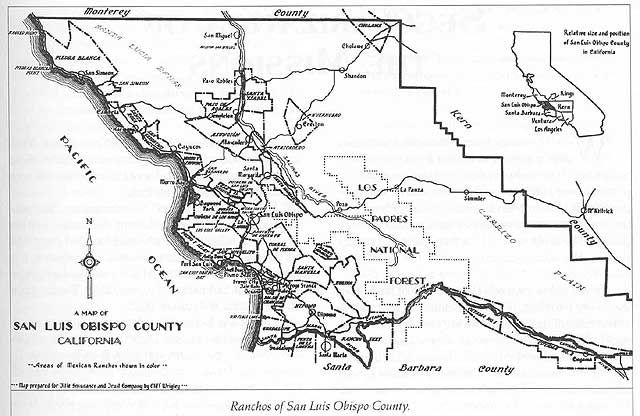

During the years of 1840 to 1846, three governors of Mexican California made grants of land from property which had belonged to Mission San Miguel. Governor Juan B. Alvarado made five grants, Governor Manuel Micheltorena made six grants, and Governor Pio Pico made three grants. In later chapters, we will look at the names of initial grantees, realizing that in many cases, other people ended up receiving the title to the property;

Governor Alvarado began the bestowing of land, which had belonged to Mission San Miguel, with the 48,805.59 acres of Rancho Piedra Blanca on January 18, 1840. Exactly one year later, on January 18, 1841, Julian Estrada received the 13,183.62-acre Rancho Santa Rosa.

Smaller acreage, of 4,348.23 acres, was awarded to Trifon Garcia in the Rancho Atascadero, by Governor Alvarado, on May 6, 1842. Three days later, on May 9, 1842, Alvarado granted Rancho Huer Huero to Mariano Bonilla.

The Rancho Huer Huero grant was of one square league, or 4,439 acres. Governor Alvarado's last grant from San Miguel land was that of Rancho San Simeon. Jose Ramon Estrada received 4,468.81 acres on October 1, 1842

The grants made by Governor Micheltorena, from Mission San Miguel land, were all made in the year 1844. The first one was the Rancho Cholame, of 26,621.82 acres, to Mauricio Gonzales on February 7th. Mauricio was the son of Rafael Gonzales- a person with whom we come into contact in other chapters.

The next two grants were made on the same date: May 12, 1844. Francisco Arce received the Rancho Santa Ysabel, of 17,774.12 acres; Pedro Narvaez received the 25,993.18-acre El Paso de Robles Rancho.

According to Blomquist, in his 1943 Master's thesis, two men, in addition to Francisco Arce, had petitioned for Rancho Santa Ysabel: Pedro Narvaez and Ezecuel Soberanes. Since Soberanes was in possession of other land, his request was not considered.

To decide which of the other two should have the Santa Ysabel, Governor Micheltorena held a conference at his residence on March 16, 1844. At the conference, it was agreed that Arce should have the Santa Ysabel, and Narvaez would be given the neighboring Rancho El Paso de Robles. Each man agreed to pay a fair price for the buildings and other improvements on their new possessions.

On July 16, 1844, Governor Micheltorena awarded to the Christian Indians of San Miguel three grants of land; they were of uncertain size and unclear location. The grants were named El Nacimiento, Las Gallinas and La Estrella. The United States Land Commission later rejected the claims to these three pieces of property because the lands had not been occupied and cultivated as required by regulations.

An appraisal was made of the abandoned Mission San Miguel on July 31, 1844. The empty buildings and nine leagues of land were evaluated at $5,875. The survey was made by Andres Pico and Juan Manso, according to Pico's Papeles varios Originates. Some of the buildings were described as being in a bad state of disrepair, a few without windows or doors, and one without a roof.

Governor Pio Pico actually made three grants from land belonging to Mission San Miguel. On June 19 1845 Pedro Estrada received San Miguel's southernmost holding, Rancho Asuncion of 39,224.81 acres. Pio Pico removed another part of Mission San Miguel's land by adding three additional leagues to Mariano Bonilla's Rancho Huer Huero. After this addition, on March 28, 1846, that rancho totaled 15,684.95 acres.

The final land grant made of the Mission San Miguel region was for ten square leagues of frontier land lying south of the Huer Huero, and east of the Santa Margarita ranchos. The land grant was known as San Juan Capistrano y el Camate. Two men, Trineo Herrera and Geronimo Quintana, were the grantees. In 1847, they built two houses near the center of the tract; they also planted wheat, barley and some fruit trees. At one time, they had 400 head of cattle on the place. Their title was later declared invalid, because it was dated July 11, 1846- four days after the conquest of Monterey by the American Forces.

This excerpt was used with Author's permission from:

The Lands of Mission San Miguel

by Wallace V. Ohles

Copyright © 1997 The Friends of the Adobes, Inc. All rights Reserved,

A copy of this book may be obtained from the Mission Gift Shop (805) 467 3256.